When one also considers that Third Generation (3G) devices will expand their share of the mobile market and that Broadcast To Handheld (B2H) such as DVB-H, DMB and MediaFlo are all vying for market share as delivery platforms for television, the stage is set for a shift from communicating to consuming and sharing rich media on mobiles.

Handset manufacturers, broadcasters and mobile operators alike have discussed mobile television and made intelligent guesses about the kinds of content that would be required. Much is at stake. For this reason, in this article I would like to pose and discuss an apparently innocuous question: Mobile TV: What Do Viewers Want?”

The results and conclusions reported here stem largely from a critical review of mobile television conducted by an interdisciplinary team including DR and the Danish Technical University (DTU) from June to December 2006, but the inferences are my own.

1. To what extent does simulcasting existing television channels on mobile platforms meet viewers?expectations and needs?

The majority of pilots and commercial launches in 2004-6 made use of existing television channels simulcast on 3G or one of the Broadcast To Handheld platforms. The DMB services in South Korea and the BT Wholesale pilot using DAB-IP did not rely exclusively on simulcast. In South Korea there were instances was different in that some programming was repackaged (in much the same way as BBC Prime contains the best of the BBC1 and BBC2) or delayed (transmitting popular programmes with an offset of an hour). BT Wholesale aimed to offer a limited number of 15-min. loops consisting of short blocks of 3-4 minutes?duration that could repeated and selectively updated.

The general consensus was that simulcasting existing television channels was what viewers wanted.

On closer inspection, we noted that the case for basing mobile television exclusively on simulcasts of such channels was not necessarily of universal applicability for the following reasons:

‧The importance of size. With the exception of the Finnish and BT Wholesale trials, all of the services were in medium-sized countries that offered more than ten television channels. Small countries often have far fewer national channels than that.

‧The availability of interesting programmes at times relevant to people on the move. Most of the trials and commercial launches simulcast programming from other television platforms. While commuters in London, Madrid or Seoul would have something interesting to watch on their way home, this would not necessarily be the case in Scandinavia with shorter working hours where people would be on their way home before early evening and prime time slots were aired.

‧Session length and picture quality. There is considerable agreement from studies and informal sources that typical mobile television sessions are around 3 minutes on 3G phones and 6-7 minutes on B2H platforms. The viewer benefits of such short session lengths would seem to be modest, apart from programming that existed in short forms such as news. Research on the use of other platforms such as handheld PVRs, MP3 players and I-Pods that can play back recorded television programmes and films indicates that session lengths are considerably greater. One of the issues reported for short sessions on 3G was the lack of transparency of the billing system and fears (sometimes justified) that extensive viewing would lead to a very big telephone bill. The display size and quality of 3G mobile services seems to be at or below a quality threshold that viewers find acceptable for sustained viewing, whereas DVB-H and especially DMB and I-Pods use higher bit rates above this quality threshold. Devices with good picture quality and no billing issues (DMB, I-Pods) were also those with the longest sessions.

‧Television alone or also radio channels? Studies such as the O2 trial in Oxford indicate that on B2H platforms, radio should not be overlooked, as more time was spent listening to radio (or in some cases the sound track of a television channel) than actually watching television. For those on the move, only those taking public transport can watch; motorists and cyclists are restricted to listening.

‧Simulcast versus On Demand/Time Shifting (i.e. synchronous versus asynchronous consumption). When considering the case for simulcast channels, it should be noted that none of the European handsets used had significant local storage capabilities. In Japan and South Korea, 3G phones (Japan) and mobile TV receivers (South Korea) have large flash memory cards allowing for downloading and time-shifting. In the Finnish trial, the On Demand sports service had a limited uptake, but this seems to have been caused more by low content attractiveness (highlights and goals from matches the previous week) than from the On Demand service per se.

‧The duration of the pilots or trials themselves. Apart from the 3 Italia, BT Movio and South Korean DMB services, the results from most of the other pilots and trials were of limited duration. If a trial has coverage in a limited geographical area for a period of a month or two, it is not surprising that viewers confine themselves to existing television channels with which they are already familiar. In the case of the German T-DMB trial in 2006, it was timed to coincide with the FIFA world Cup in Football.

2. What content categories are mobile viewers interested in?

The first European studies ranked content genres. Invariably news was at the top, usually followed by entertainment, music or sport. The BT Wholesale pilot built on extensive audience research on broadcast and downloadable content and went to great lengths to enter into agreements allowing for the repackaging of News, Sports, and Entertainment in fifteen-minute loops.

However, a study for RedBee conducted by iBurbia [2006] suggested that full length programming on mobile is not as popular as content made for mobile TV because screen sizes are too small, opportunities to watch full length programmes on-the-go are rare and subjects preferred to watch full-length programming on the TV.

Nigel Walley, CEO of Decipher, which owns iBurbia was quoted as saying: 浠e talked with a broad range of people in this study and there was significant interest in concepts that complemented TV viewing with extra and exclusive content on mobile phones. But the content had to be sufficiently compelling to be worth the effort and there is a fear of billing abuse, meaning that cost needs to be made clear.

Further work is clearly needed to explain these conflicting results.

3. What are mobile viewers prepared to pay?

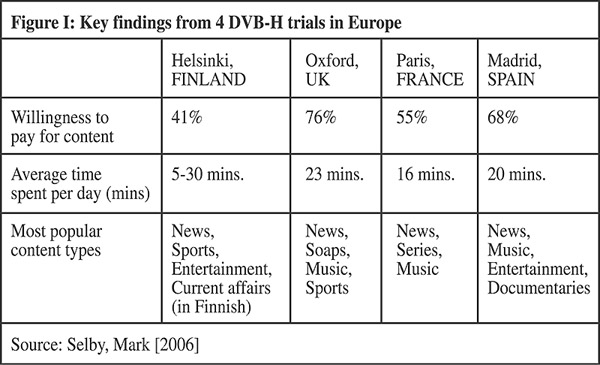

For the European studies referred to earlier indicated that mobile viewers are indeed prepared to pay what they watch (Figure I).

A more detailed scrutiny of the results indicated that the figures needed to be used with caution:

‧Samples. The sample used in the Finnish trial was skewed to provide what was thought were the early adopters of such services, so those taking part are predominantly males between 20 and 40 years of age. The figure cited is thus 41% of the sample, not of the Finnish population. The Oxford trial is not a representative sample, although the age range used is greater. Secondly, the panel was asked about its views before actually using the service.

‧Methodological weaknesses. Those questioned just indicated whether they would be interested in such a service without any mechanism to make such a statement binding in any way. The figures are thus general indicators.

3 Italia have offered a full-blown service and in this respect, consumers are voting with their feet by subscribing or not subscribing. Generalising on the basis of Italian results is difficult, however, because of the many special offers and the subsidised handsets.

In the case of T-DMB, the payment issue is not relevant, as the B2H is paid for by advertising revenue. T-DMB is available on mobile phones, on handheld TV receivers and on T-DMB receivers that can be mounted in cars and taxies.

In a study concluded in Stockholm in 2007, participants were told that they would be able to trial the service for two months after which they could choose to subscribe to the service for a monthly subscription of SEK 50/EUR 5/HKD 50. They were told they would also have to pay for the handset. In the event, the operator gave participants the handset but the trial set up did provide a more reliable framework for gauging willingness to pay,

4. What is known about the physical context in which viewers watch mobile television and to what extent does it determine the viewer’s needs?

All of the studies that were reviewed looked at the physical context in which mobile television was used. Generally speaking, mobile television viewing was studied in the home, at work and on the move. A feature common to the European studies was that mobile viewing in the home is more prevalent than on the move, whereas it is less so in Korea.

Short [2006] reflects on what he terms the contextual user environment (CUE) (including travelling by car, walking around a shopping mall, in the street and on the bus, at home and in the office and the importance of understanding how the user’s physical environment influences their mobile technology needs.

Some of the anthropological studies are gone considerably further and have studied mobile viewing in a plethora of physical contexts. Chipchase et al [2005] and Chipchase et al [2006] provide detailed observations of mobile use and the interplay between physical context and needs.

As part of my own work, I searched Fickr for photos of pockets and purses, and came to broadly the same conclusions as Ichikawa et al [2005] that provides statistics on mobile devices and where these are carried by their owners. The results show a strong gender differences, with women using bags and purses and men using trouser pockets to keep their mobile phones.

Taken together, it seems that mobile television is a misnomer. It would be better termed ‘personal pocket media’ or ‘personal purse media’, given the location of the device and the range of media ?not just TV ?that are accessed. It also seems that are assumptions about watching television on the move may be exaggerated. Multi-functional mobile devices allow their owners to entertain themselves or just ‘kill time’ to keep informed and to keep in touch with those who are important to them. Mobile media on the move and in the home are considerably influenced by culture. A fuller understanding of home use is imperative, certainly for European users.

5. Will multifunctional mobile phones offering mobile television dominate the market or complement the existing range of handheld devices capable of displaying television and video?

Handset manufacturers such as Nokia and Samsung are certainly working towards this scenario, but several studies indicate that in terms of business models, technological performance and user attitudes, television may also be viewed on a range of devices for some time to come.

‧Business models. 3G networks have been operational for just a few years and operators need to assure a return on their investment before offering B2H services on a subscription basis only. Although there are problems with picture quality and assuring the necessary network quality of service when multiple users all want to stream TV content in he same cell, there are solution that both increase the effective bandwidth and allow the operator to switch from streaming to multicast. Even so, there are lingering doubts about delivering television over 3G networks.

‧Technological performance. Battery life, good screens that do not need power-hungry back lighting, indoor reception, good and fast user interfaces and transparent billing are all hurdles yet to be fully overcome before personal pocket or purse media can take off in a convincing fashion

‧User attitudes. For the time being, studies such as Umbria’s Mobile TV Report [2006] for adults and Ali [2007] on children point to current preferences for dedicated handheld devices rather than a multifunctional mobile phone. But on the other hand, given that such devices are usually kept in pockets or purses, it is not unreasonable to expect some competition for a place in that pocket or purse. Ultimately, a well-engineered handset that offers all-in-one convenience should lead to changing attitudes.

Conclusion

There seems to be no doubt that television will be accessible on mobile devices. The issue is what kind of television, when it will take place and who is going to pay for the costs of establishing and operating the service. This article indicates that a strategy for mobile television based exclusively on simulcasting existing channels has limited potential, especially in small countries. Only by making a concerted effort to understand the way in which the viewer’s physical context influences his perceived needs will it be possible to offer personal pocket and purse media in an economically-sustainable way.