Experienced journalists who work to tough deadlines have first-hand knowledge of editorial processes that shape news. Those who watch or listen to news at the top of the hour, or are readers of news on the Internet or in newspapers may be less familiar with the work flows that affect news items that get to the viewer, listener or reader. And yet very few journalists or informed readers are aware of some of the new mechanisms influencing news. What these influences are, how they work and who initiates them are termed gatekeeping and they are what this article is all about.

Gatekeeping - applying the metaphor

The metaphor of gatekeeping triggers mental images of city gates controlling access to walled cities. Such walled cities were widespread in China and in Europe and many of them survived until the 18th or 19th century.

Common to all walled cities was the presence of a gate - sometimes more than one - built into the wall to provide a point at which access to and departure from the city could be controlled.

Gatekeeper control affected everyone who entered and left the city. The gatekeeping mechanism was typically a portcullis that rapidly could be raised and lowered, and gates that could be closed and secured at night-time or in times of emergency. In some cities there were additional gates within the city to control access to and from the keep and other buildings of strategic importance.

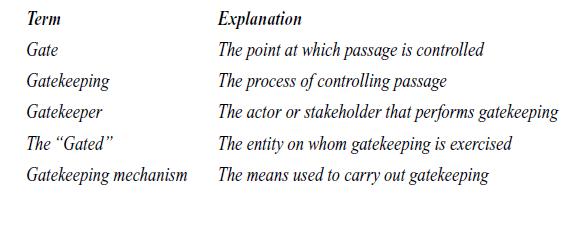

The area in and around the main city gate was often used for dissemination. Announcements and proclamations, information on tolls and taxes, weights and measures were all displayed here to inform passers by. To apply the metaphor we need to understand 5 key terms and how they are related. Barzilai-Nahon makes the following distinctions:

Studies of gatekeeping and news started nearly 60 years ago originally focused and applied the metaphor to who was involved in the editorial processes shaping news. Shoemaker and Vos in their book on gatekeeping note that this controlling of news involved gates within a news organisation and established that gatekeeping takes place at several levels:

• At the level of the individual journalist or employee acting as a gatekeeper in terms of the production and selection of news items from external sources

• Collective gatekeeping in the form of explicit or implicit communication routines (“news-worthiness”, policies about the use of official or formal sources and the backwash effect of deadlines and the logistics of having to go on air with the news)

• Organisational gatekeeping (e.g. organisational socialisation which leads to news staff adopting the value system of the new organisation that employs it and the groupthink phenomenon in which the pressure to reach consensus may override the contributions of individual members of staff).

We can think of these processes as being internal gates within a walled city regulating movements in and out of a particular building with a variety of gatekeepers (individual journalists or editors) and both formal and implicit gatekeeping mechanisms.

News organisations are part of a media ecology that involves interaction with other organisations or external stakeholders. The interface with the outside world can be thought of as a gate in the city wall.

For commercial media such as commercial television channels that carry advertising, the organisation has two customers: viewers who watch the TV-programmes and brand owners that place advertising that will be seen by various audiences segments. Ultimately, the TV station has to balance the interests of both its viewers and its advertisers to survive. Gatekeeping mechanisms for news will have to handle commercial agendas and imperatives in a way that does not endanger the perceived credibility and trustworthiness on the part of the viewers.

The external gate may also involve some kind of regulation of the news through bodies such as a press council or a government agency with some direct influence over the publication of news or the handling of “right of reply” legislation, and civil courts to handle cases of libel or slander. The issue here is whether regulation takes place in the open under clearly-defined and transparent rules (the “main gate” of our metaphor), or whether it takes place in an ad-hoc manner lacking in transparency (as if it were a gate concealed in the main wall through which passage was effected in the black of night).

Ties the gated to the gatekeeper

In terms of being able to watch TV channels that are broadcast free-to-air on digital terrestrial transmitters, at first glance there appears to be no “main gate”. A consumer can go into a consumer electronics retailer on the high street and buy just about any brand of terrestrial receiver he likes. It can be an integrated digital TV receiver or just a set-top box that can be hooked up to the existing TV receiver. Once there is a signal from an aerial or dish and the receiver has been tuned, the consumer can go ahead and watch any of the free-to-air channels available in the area.

In the case of pay-TV, the main gate is usually the television receiver itself. The gatekeeper is the Pay-TV operator who charges for access to various programme bundles, some of which will contain a mix of general channels and “premium” content such as channels, sporting events and films not available from other Pay-TV operators.

The gatekeeping mechanism is usually technical. The operator requires the subscriber (the “gated”) to acquire and use specific hardware and software to receive its television service. This is either a conditional-access unit requiring a smart card provided by the operator to be able to see encrypted programmes, a set-top box with a specific application programming interface (API) and technical features meeting the requirements of the operator, or both.

This technical gatekeeping mechanism - investing in the necessary hardware - is to get the user to pay a subscription for the service. This means that a potential customer needs to weigh up the perceived value of the Pay-TV television service against the extra visible and invisible joining costs of having to rent or buy hardware and the exit costs should he choose to leave the service.

The joining cost can create an economic barrier that prevents “churn” - viewers switching to a competing pay-TV service. In the UK, a subscriber would find it costly to switch from BSkyB to Virgin Media, as this would require getting a new set-top box and perhaps even a new personal video recorder (PVR) as the old satellite box and PVR are incompatible with Virgin requirements.

Churn is a significant expense for operators. Anything that reduces annual churn rates also keeps costs down (both investments made in equipment and services for the departed customer but also the additional costs of having to “recruit” a replacement customer).

This kind of gatekeeping mechanism that ties the gated to the gatekeeper makes it attractive for operators to invest in new services. When BSkyB launched its Sky+ personal video recorder, churn among existing customers reportedly dropped to half its previous rate, improving Sky’s earnings. The popular Sky+ PVR service was an added inducement to keep subscribers loyal to the operator. The perceived value of the service far outweighed the additional future exit costs for the subscriber.

The clear differences between Pay-TV and free-to-air TV may become blurred with the introduction of hybrid television receivers that have both digital broadcast and broadband connections.

At the end of 2008, Samsung announced a new range of hybrid television receivers for the European market that allowed the viewer to view widgets with various Internet services overlaying the television signal. Samsung had made an agreement with Yahoo to provide news widgets on such screens.

Imagine the situation where you as a TV viewer tune to the BBC in order to catch the main evening news. While waiting, you choose the digital text or browser option to catch up. Instead of seeing BBC’s digital text news overlay, you are offered Yahoo news widgets. You switch to a competing news channel, Sky News and again are offered Yahoo widgets rather than Sky’s. It is not surprising that this incident was the source of considerable concern among broadcasters, as were the hybrid broadcast-broadband initiatives of other consumer electronics manufacturers.

In the Samsung case, the gatekeeper was the manufacturer of the television receiver. The gate was the television receiver with a broadband connection, but the gate itself was concealed from the consumer (the gated) who may not have known of this feature until after having purchased the set. Gatekeeping in this case involves the pre-selection of news widgets that the viewer cannot change and that are in potential conflict with comparable services from the broadcaster to whom the viewer is tuned.

The widget agreement between Samsung and Yahoo was almost certainly drawn up with the best of intentions, but the lack of transparency and the implications of “hard-wired” news services using widgets are a source of concern.

As we have seen, there are gates both within a television organisation and elsewhere within the television value chain. In some cases the gates, the gatekeepers, the gated and the gatekeeping mechanisms are clearly visible and their impact is clear to see.

What characterises digital media in the current decade compared with those of the 20th century is the fulfilment of the “anything, anytime, anywhere and on any device” paradigm. Customisation is not enough. In order to succeed, digital media need to offer personalisation – even when we talk about social media.

What the examples quoted earlier about gatekeeping and digital television demonstrate is that control mechanisms are in place at numerous points and levels. Gatekeeping is not a one-way process, in that gatekeepers and the gated exert influence on each other.

The challenge is not one of more or less gatekeeping, but rather to ensure that journalists and citizens alike have a solid understanding of the way in which digital media are planned, produced, distributed and consumed. Transparency about gates, gatekeeping mechanisms and their impact is one of the main prerequisites for a harmonious society, and one which will become ever more difficult to assure as new media devices, networks and value chains emerge.

This is an abbreviated version of a forthcoming essay on gatekeeping to be published by the Open Society Foundation’s Media Program. The essay and others in the same series can be accessed later this year at www.mediapolicy.org