Massive investigation of Don Bolles murder was unique in American journalism history.

Massive investigation of Don Bolles murder was unique in American journalism history.Don was a reporter for The Arizona Republic. With a daily circulation of some 340,000, the Republic was the largest daily in the American southwest. It also was staunchly conservative. The paper was owned by Eugene Pulliam, maternal grandfather of Dan Quayle, U.S. vice president under the first Bush presidency. But the newspaper nevertheless had outstanding leadership on the editorial side. It was known for reportorial excellence.

Don was 41 when I met him in 1970. He was a mild-mannered, pipe-smoking family man with seven children. As a reporter, he was distinguished by his reporting techniques.

While most of us in the newsroom got bylines every day, Don's bylines were infrequent, and his stories were so long and rich and detailed that they were arcane to some readers, even me. One needed a background in law and finance to understand some of his work, especially his articles on land fraud and on greyhound racing in Arizona.

Don recorded all of his telephone conversations and personal interviews, and he saved all the audiotapes in anticipation of legal action. He also saved all of his reporter's notebooks. Sometimes, when he went out for a face-to-face interview, he would write details of the meeting on a sheet of paper -- time, place, name of interviewee -- and mail it to himself, in the event of his disappearance. When he parked his car, he often placed a pebble or a piece of cellophane tape on the hood so that he would know if someone had tampered with the engine.

Don was an investigative reporter. In fact, he was a founding member of Investigative Reporters and Editors, America's pre-eminent club for investigative journalists, and these were some of the techniques he used to protect himself from continual threats of lawsuits and murder. The death threats were not directed solely against him, but also against his wife and children. It was only the threats against his wife and children that raised doubts in his mind about his line of work. His own life seemed of little consequence to him. In this way, he seemed unusually courageous to me.

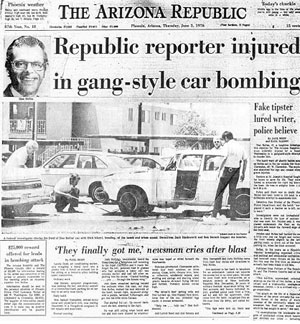

One morning in early June of 1976, Don was working in the press room of the Arizona State Senate building when he received a telephone call from someone asking Don to meet him for lunch in the lobby of a hotel in downtown Phoenix. Don went, but his lunch companion did not show up. After waiting for some time, Don returned to his car, a white Datsun sedan. It blew up in a horrific explosion. Police later said explosives under the driver's seat had been detonated by remote control radio

Don's maimed body was lying half in the car, half on the pavement. The temperature was 100 degrees Fahrenheit. He was still alive. He survived in hospital for more than a week. His arms and legs were amputated. He was a mere torso when he died on 13 June.

Assassinating Don Bolles was one of organized crime's biggest mistakes. Headed by Bob Greene of Newsday, Investigative Reporters and Editors sent 38 journalists from 28 newspapers and television stations to Phoenix to investigate Don's murder. They were driven by a sense of outrage. The result was a 23-part nationwide newspaper series and a book, The Arizona Project. IRE's massive investigation was unique in American journalism history. Organized crime today in Arizona is a shadow of its former self.

Absence of a Tradition of Investigative Reporting in Hong Kong

Don Bolles was not unique. The United States has a large and dynamic community of investigative reporters. Due to their work on the Watergate investigation in the early 1970s, The Washington Post's Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were immortalized in the film All the President's Men', which is recommended viewing. Then there is Seymour Hersh, who established himself by uncovering the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and subsequently wrote The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House'. A more recent example is the late Randy Shilts of The San Francisco Chronicle, whose book And the Band Played On' uncovered the U.S. government's callousness and ineptitude in handling Aids.

In fact, the numbers of men and women dedicated to investigative journalism are many, but I do not find a tradition of investigative reporting in Hong Kong. In my personal view, a noteworthy feature of the press in Hong Kong is the absence of strong investigative reporting. This is especially unusual given the highly competitive nature of the newspaper market and the freewheeling attitudes of some business tycoons here with close ties to government.

For the record, I should provide a definition of investigative reporting. Here is one provided by IRE's Bob Greene:

It is the reporting, through one's own work product and initiative, matters of importance which some persons or organizations wish to keep secret. The three basic elements are that the investigation be the work of the reporter, not a report of an investigation made by someone else; that the subject of the story involves something of reasonable importance to the reader or viewer; and that others are attempting to hide these matters from the public.

As I said, I don't see much of this in Hong Kong, but I know that my view will offend some journalists. I recognize some journalists and their excellent investigative work; indeed, some of them are friends of mine, and we have discussed their investigative techniques.

I'm talking about a tradition of investigative reporting, however, not occasional investigative reports. A tradition is an established way of doing and thinking about things, an outlook or approach that may be passed from one cohort to another by organizations whose purpose it is to maintain these traditions.

Institutional and Legal Supports

Drawing on my experiences in the U.S., here are some of my views on why investigative journalism is not a tradition in Hong Kong:

For one thing, the United States has excellent institutional and legal supports for investigative journalists that Hong Kong lacks. By institutional supports, I mean organizations such as Investigative Reporters and Editors, but there are many of these. The Center for Investigative Reporting is another example. Other nations have them as well. In the Philippines, for example, there is the Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism. In Russia, a most unlikely place to find something like this, there is the Agency of Journalist Investigations in St. Petersburg.

Other institutional supports in the U.S. include prestigious awards. In America the most prestigious prize is the Pulitzer Prize, and there is a special category of Pulitzer for investigative journalism. Yet another type of institutional support is print and broadcast media that specialize in publishing investigative reports -- Ramparts, Mother Jones, the Progressive, even The New Yorker and The New York Times Sunday Magazine. There are dozens of these in the U.S.

By legal supports, I mean laws that favor journalists. The best known is the Freedom of Information Act, which exists at the federal level and gives total access to a truly incredible number of government documents. Similar laws, sometimes known as Sunshine Laws, exist at state levels in the U.S. Also, because investigative reporters must rely on anonymous sources for much of their work, some courts in the United States actually protect journalists from having to reveal the names of anonymous sources in court proceedings. While this is not commonplace, it is indeed extraordinary that some courts protect journalists in this way.

In addition to institutional and legal supports, the U.S. has a rich and varied history of investigative journalism. Some of the greatest names of 20th century America are recognizable because of their investigative journalism -- Upton Sinclair, I.F. Stone, Drew Pearson, and, more recently, Jack Anderson, Neil Sheehan, Bob Woodward. Journalism graduates of American universities are familiar with these names, and the students thus recognize investigative reporting as a journalistic tradition in their country.

Lack of Training

Finally, I suspect that the education system in Hong Kong does not prepare students well for this kind of career. At the primary and secondary levels, there is the much discussed, lockstep educational approach that focuses exclusively on examination results, and this does not provide training in analysis and reflection, which are important skills for an investigative journalist. At the university level, journalism students in Hong Kong are required to take far more courses in journalism departments than they are in the U.S., where they are expected to do much more coursework in the social sciences -- economics, political science, sociology and so on. Not to mention that university programs in the U.S. are four-year programs, while they are only three-year programs here in Hong Kong. Generally speaking, Hong Kong journalism graduates do not have enough training in relevant fields to understand the forces at work in society.

In summary, I see significant differences in the sociology of journalism between the U.S. and Hong Kong that make America a more fertile ground for this kind of reporting. Once they have been made aware of these differences, however, Hong Kong journalists can work to achieve a better climate by making changes in the appropriate directions.