In Tunisia, Astrubal trolled amateur planespotting websites and discovered that the presidential plane had been photographed in the airports of Europe’s shopping capitals. How could that be, he asked, when the president had never taken an official trip overseas? The answer: The First Lady was an avid shopper.

Satellite images from Google Earth helped Mahmood’s Den plot the vast expanses of land that had been awarded to members of the royal family in Bahrain. Google Earth also enabled Burmese exiles to locate Naypyidaw, the secret capital built by the country’s ruling junta. They uploaded the images onto YouTube, a short clip that showed the palatial homes of junta members and the gigantic swimming pool built by the dictator Than Shwe. Few Burmese have Internet access, so the video was copied on discs and smuggled into the country.

Is this the dawning of a Golden Age of global muckraking?

Since the 1980s, there’s been an explosion of exposure journalism in countries that until recently did not even have a free press. The fall of authoritarian and socialist regimes has opened up spaces for accountability reporting, allowing journalists in many new democracies to become one of the most effective checks on the abuse of power.

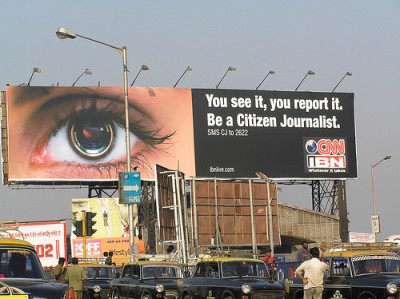

In the last decade, new tools like blogging software, Twitter, Google Earth and YouTube have become widely and freely accessible. These have democratized muckraking in ways previously unimagined. Empowered by the Internet, bloggers like Malyutin,Astrubal and Mahmood Nasser Al-Yousif of Mahmood’s Den are piercing the veil of official secrecy. Like the nameless Burmese exiles who commit occasional acts of journalism, they show that the watchdog function is now no longer the sole preserve of the professional press.

In Europe and North America, there’s been much wringing of hands about the uncertain future of investigative reporting. This is especially true in the US where, since Watergate, newspapers have been the keepers of the investigative flame. With many newspapers at death’s door, there’s worry about whether they can keep the flame alive.

But elsewhere, democracy and technology are prying open previously closed societies and providing citizens with information that would not have been available to them in the not-too-distant past. From Bahrain to Burma, from Russia to China to Zimbabwe, the new muckrakers are using blogs, mobile phones and social media to expose the predations of those in power. he truth is that, in most of the world, there has not been much watchdog reporting until recently. In these places, therefore, the concern is not so much the business model that would sustain investigative newsgathering.

It’s whether journalists and citizens who expose wrongdoing can stay alive or out of prison. Muckraking journalists and citizens have been sued, jailed, beaten up and killed.

In Russia, contract killers have gunned down investigative journalists in their homes or on busy city streets. In Mexico,journalists have been murdered by drug cartels; in the Philippines, the assassins have been rogue cops and soldiers linked to local bosses. As watchdogs breach the bounds of what’s possible to publish, the backlash will surely be fierce.

Yet, a return to the Dark Ages no longer seems possible. The openings we see today are here to stay and provide us a glimpse of a possible future for accountability reporting.

In an increasingly global and networked world, watchdog reporting will cease to be the monopoly of professional news organizations. It will be a much more open field, which journalists will share with individuals, research and advocacy groups, grassroots communities, and a whole slew of Web-based entities like WikiLeaks, for which a category and a name have yet to be invented.

As commercial media search for a business model, professional, high-quality investigative reporting will increasingly be subsidized by foundations and the public, and in some countries, even by taxpayers. Freed from market pressures, nonprofit investigative reporting centers will be doing groundbreaking reporting. There are already a few dozen of them in Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America and Asia.

Technology will enable news organizations to produce increasingly sophisticated investigations using large amounts of data and presented in amazing new ways, especially as governments, companies and international organizations make more and more data publicly available.

The future of investigative news will be collaborative. Strapped for resources, news organizations will be forced to cooperate, rather than compete. Joint investigations involving several news organizations, for profit and nonprofit entities, professionals and amateurs, across media platforms and across borders will be commonplace. Crowdsourcing will be the norm, with audiences initiating and taking part in investigations.

Like elsewhere in journalism, investigative reporting will divide into niches. Communities of interest will form around various areas of watchdog reporting. These could be consumer concerns or national security or something more specific, like watchdog sites to monitor the whaling industry or the safety of bridges.

The future of investigative news will be local, as communities drill down on local concerns. Web-based local watchdogs will set up small newsrooms specializing in accountability reporting and funded by a mix of commercial revenues and community support.

But the future will also be global. There will be much more transnational reporting on such issues as crime, corruption, the environment, and the flow of goods, money and people across borders. Journalists and citizens will be collaborating across borders like never before, using the tools of the networked information age.

Such collaborations are already taking place; in Europe, Africa and the Arab world, recently formed regional investigative reporting centers are bringing journalists together to work on cross-border projects. An international consortium of investigative journalists has created reporting teams to probe issues like tobacco smuggling and asbestos use.

Watchdog reporting will also likely take on new, unorthodox forms. In China, journalists are resorting to microblogs, posting sentence fragments, photos or videos online, often through mobile phones, in order to break controversial stories and evade censorship.

In the US, advocacy groups are developing mobile phone apps that enable users to have easy access to data, such as Googlemapped government-funded projects or hazardous ingredients in everyday products.

Various ways of providing information will likely emerge, sometimes in unexpected places, like video games. Innovation and experimentation will characterize this new era.

But the future also bodes more intense clashes between watchdogs and wrong-doers

Yet muckrakers will likely plod on even in the most inhospitable environments. Wherever power is abused, the compulsion to expose wrongdoing will likely remain strong. But so will the determination to quash exposés. If not violence, watchdogs will be subjected to legal bullying. In China, dozens of reporters and bloggers have already been jailed for a range of offenses, including libel and exposing state secrets.

In the geography of threats, cyberspace is the new frontier. Already, the Internet has encouraged libel tourism, the practice of suing journalists in overseas jurisdictions where laws are more onerous, on the grounds that what’s published locally has a global audience online.

The great battles between secrecy and transparency will be fought on the Net. As watchdogs expose individual and institutional wrongdoing, there could be a backlash against openness, with governments clamping down while invoking the need to protect privacy, public safety or national security. There could be some public support for a crackdown if muckrakers report irresponsibly, but it would be difficult to sustain such support once citizens have tasted the benefits of openness. The emerging terrain is one suited to guerrilla warfare. The Internet provides many safe havens. And as the Chinese have shown, savvy netizens find ways to outwit government restrictions. With the ubiquity of mobile phones, proxy servers and other devices, a total clampdown is no longer possible. Moreover, technology makes it easier to mobilize protest.

Like all journalism, the landscape of watchdog reporting is being radically altered. It will be a contested and uneven landscape. Powerful governments and individuals will try to muzzle watchdogs. Vested interests may fund pseudo-watchdogs to counter those who would hold them accountable. Some places will have a thriving community of muckrakers; others will be bereft.

Some voices will be lost in the wilderness of cyberspace. But many watchdogs will have impact, becoming influential voices in their communities and around the world.