As of this year, 122 firms possessed licenses from the Office of the Telecommunications Authority to provide Internet services. Getting a license is a neutral and transparent process. Application forms and a paper explaining the registration process are online on the OFTA's web site(www.ofta.gov.hk)To register as an Internet Service Provider, or ISP, one needs to meet only minimal technical requirements and pay a small fee.

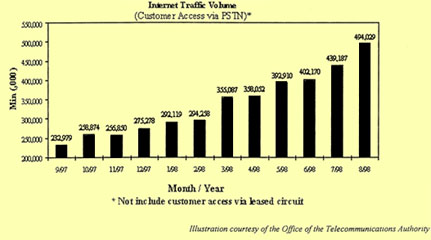

Internet traffic in Hong Kong has grown markedly, more than doubling in the past 12 months. One could assume that abuses of Internet privileges have grown as well. Indeed, there have been some high profile prosecutions for postings of pornographic content. Nevertheless, there is a mistaken and widely held view among policymakers that the Internet cannot be regulated. The purpose of this article is not to argue for regulation, but simply to set the record straight: The Internet can be regulated at many levels and in many ways.

Much of the following focuses on the control of obscene and indecent materials, the main concern of the SAR government; however, one could easily extend regulation to cover any kind of content whatsoever.

Background

Calls for regulation surfaced in 1995. In December, an interdepartmental working group was set up. This group represented the Broadcasting, Culture and Sport Branch, the Economic Services Branch, the Legal Department, the Office of the Telecommunications Authority, and the Television and Entertainment Licensing Authority.

On 10 July 1996, the Broadcasting, Culture and Sport Branch issued a consultation paper entitled "Regulation of Obscene and Indecent Materials Through the Internet". The consultation paper suggested creation of an Internet Service Providers' Association and called for a self-regulatory scheme that would include an industry code of practice and a complaints handling system.

On 21 January 1997, the results of the consultation exercise were published by the Broadcasting, Culture and Sport Branch and the Legco Panel on Information Policy. Principal concerns included the following:

* Free flows of information and freedom of expression;

* Protection of public morals and young people;

* Effect of regulation on development of information infrastructure;

* Effectiveness of any regulatory scheme.

A key paragraph contained the following sentence: To attempt, actively, to monitor content on the Internet would be impractical and unproductive. This statement reflects public pronouncements made to the press by policymakers at the time of the consultation exercise.

Facing the prospect of regulation if they did not form an alliance and develop a Code of Practice, several Hong Kong ISPs formed the Hong Kong Internet Providers' Association in mid-November 1996 (www.hkispa.org.hk). The HKISPA adopted a one-page Code of Practice on 12 April 1997. The code said its adoption was voluntary, and it made no reference to the control of obscene and indecent material. While the Code of Practice makes no reference to the control of pornography, there is another HKISPA document entitled "Code of Practice: Practice Statement on Regulation of Obscene and Indecent Material" that provides some detail on what can and cannot be put on the Internet.

The Practice Statement lacks teeth, however. It prohibits users from posting or transmitting Class III materials, as defined by the Control of Obscene and Indecent Articles Ordinance. And it calls for a warning to people under the age of 18 to accompany Class II materials. When an ISP realizes that a user has put up Class III material on the Internet, the ISP is required to:

* Block access to the web site or database containing the offending material;

* Inform the user that the user's conduct may constitute an offence under the COIAO;

* Cancel the account of any subscriber that repeats offending conduct;

* Report the matter to the HKISPA on action taken.

A notable omission is that the ISP is under no obligation to report such incidents to the police as criminal matters - even though posting Class III material on the Internet is quite likely a violation of the COIAO. This observation is not meant as a criticism of the HKISPA or the Code of Practice, but is merely an attempt to illustrate the lack of regulation.

In the absence of regulatory policy in Hong Kong, one finds piecemeal attempts to fill the void. For example, until recently, the Television and Entertainment Licensing Authority maintained a list of 1,000 "objectionable websites" and made the list available to ISPs. The Department of Education maintains similar lists, and such sites are blocked in schools. Also, as noted above, the HKISPA has a well-elaborated policy on posting Class II and Class III materials. And even individual ISPs have various policies on blocking sites. Finally, there are high profile prosecutions - such as the case of the 24-year-old Japanese computer engineer who was sentenced in March to 21 months in jail for posting 43 pornographic pictures of children.

The Experience of Other Nations

Once again, it should be noted that the purpose of here is not to argue for regulation, but merely to point out that regulation is possible. The experiences of Singapore, Vietnam, China and the U.S. are noteworthy.

CHINA

According to the China Network Information Center, 1.8 million people now have some form of access to the Internet in China. China has had stiff regulations since February 1996. At that time, the State Council Electronic Information Leading Group issued a series of directives. These directives:

* Promulgated a list of 100 sites to be blocked, including The Far Eastern Economic Review, Playboy magazine, The South China Morning Post, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, the Hong Kong Democratic Party, the Dalai Lama Tibetan Exile Page, The Journalist and China Times (both of Taiwan), CNN, and the Taiwan Government Information Office (but it should be noted parenthetically that this list of blocked sites is frequently amended, with some names deleted and others added);

* Put the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications in control of all overseas communications;

* Ordered monitoring by the MPT (domestic and general overseas traffic), by the Ministry of Electronics (computer companies and network entities), by the State Education Commission (universities) and by the Academy of Sciences (research institutes).

* Required ISPs to adopt screening software to filter out pornography and counter-revolutionary content;

* Gave the State Council power to approve all new networks;

* Ordered subscribers to sign a document at their local Public Security Bureaus promising they would not use the Internet to produce, retrieve, duplicate or spread information that may hinder public order.

In August 1998, CNIC signed a bilateral agreement with Network Solutions, the Internet domain naming authority, to take over domain naming responsibilities for.com, .net, .org and .cn domains. This important responsibility gives Chinese authorities control over who can provide Internet access, because the domain name is a computer's address in the network: Without an address, it lacks connectivity.

Naturally, there are ways successfully to "abuse" Internet privileges in China. A case in point was the well publicized arrest of a Shanghai businessman who provided 30,000 Chinese email addresses to a dissident site in the U.S.

A countervailing force is the so-called Internet cafe, where one can get an hour's access to the Internet for a mere 20 yuan. Stan Sesser, a senior fellow at the Human Rights Center of the University of California at Berkeley, said the explosion of these in urban areas has provided Internet access to everyday folks. Students and young professionals are typical customers, but their main interests are dirty pictures and overseas educational opportunities - not counter-revolutionary content, according to Sesser.

VIETNAM

With 78 million residents, Vietnam is the world's 12th most populous nation, but the immediate market potential of the Internet was recently estimated to be only about 10,000 subscribers. Penetration is low because of the lack of infrastructure and because the government worries about Vietnamese expatriates who might use web sites to foment unrest. Of all nations in Southeast Asia, Vietnam, even after a decade of reforms, is among the strictest in terms of controlling public access to information. Satellite dishes are banned, one must declare publications in one's possession when entering the country, and access to overseas Internet Service Providers by telephone links is prohibited.

Prior to this year, Netnam, a nonprofit government agency administered by the Institute of Science and Technology - the Institute is a state run agency under the National Centre for Natural Sciences and Technology -- was the main ISP in Vietnam. All Internet users were required to register with Vietnam Posts and Telecommunications, and users were required to comply with press and publication laws. Violations could result in fines and prison sentences.

The situation changed radically in early 1998, however, when four Vietnamese companies -- Vietnam Data Transmission, Saigon Postel, Finance Promoting and Technology Company, and the Information Technology Institute - were authorized by the government to provide Internet access, although the government said citizens must visit only "culturally acceptable" sites. The Internet cafe phenomenon has reached Vietnam as well as China, according to Sesser, who has traveled widely in China, Vietnam and Singapore studying people's use of the Internet. Sesser reported that, while dissident sites such as www.free.viet.org, www.vietgate.com and www.saigon.com are blocked, one's behavior in Internet cafes is generally unmonitored: No identity card is required to use the facilities, there is no supervision, and there is no concern about what is accessed.

SINGAPORE

Some argue that Singapore's attempt to control Internet content has been successful. Singapore's main regulations went into effect on 15 September 1996. They included restrictions on anti-religious sentiment, racism, material that would "excite disaffection against the government", obscenity, pornography, and gambling. Additionally, encryption software cannot be used unless registered with the government.

To expedite control, the government licensed only three ISPs - Singnet, Cyberway and Pacific Internet. In all three, the government is either owner or controlling partner. These ISPs use proxy servers, or servers that run parallel with the main web server. The main purpose of a proxy server is to store information accessed by the main server, thus saving time and money while retrieving data from frequently accessed sites. The proxy servers are monitored by the Young PAP, which reports to the government, and there have been some well publicized cases of arrests and prosecutions, putting users on notice.

Singapore, by the way, has a two-track policy on telecommunications. Businesses can own satellite dishes, while individuals cannot. Businesses can have unrestricted access to the World Wide Web, while individuals cannot. One outcome of this, according to Sesser, is that people browse for pornography at the office rather than at home.

Different countries have their own experiences and means to control content on the Internet. |

U.S.

The United States has grappled with these issues, but unsuccessfully. The main attempt at regulation was the Communications Decency Act of 1996, passed by both chambers of the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton. The law made it illegal to post porn on the Internet in such a way that it would accessible to children under 18, and violators faced two years in prison and a US$250,000 fine.

In June 1997, the law was struck down by the United States Supreme Court because it was "too general" and thus incompatible with the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The full text of the First Amendment follows: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." Period.

Two points can be made about the American experience: One is that Hong Kong does not have a First Amendment, so the United States' Communications Decency Act, if adopted by the Hong Kong government, would not be struck down by the courts. The other is that, while the Communications Decency Act may have been at odds with the First Amendment, the problem had to do with the phrasing of the law. It is quite likely that a subsequent attempt by the U.S. to regulate pornography on the Internet will be successful. Surely the U.S. Congress has learned from its experience.

Options for Regulation and Controls

We now come to the heart of this article, which is a list of means to control content on the Internet. These are drawn from the experiences of the countries surveyed above, as well as Hong Kong's own experiences:

* High profile prosecutions of people who abuse Internet privileges. These have taken place in Singapore, China, and Hong Kong.

* Limits on the number of ISPs. This is the case in most of the countries surveyed. This makes screening and monitoring of content easier.

* Monitoring of content, such as is done in China and Singapore. This would not necessarily be extensive, but "spot checks" whose purpose would be to remind users that their behavior is subject to observation by authorities.

* Screening software. Vietnam and China both have contracts with U.S. communications giant Spring to provide screening software.

* Prohibitions against encryption software. In Singapore, encryption software must be registered with the government.

* Restrictions on the kind of content that may be accessed. Pornography and dissident web sites are obvious targets of some governments, especially Singapore, China and Vietnam.

* Proxy servers to store large quantities of data - text and graphics - from accessed sites for later perusal by authorities. Proxy servers are already in wide use in Hong Kong. Their purpose in Hong Kong is not surveillance, but to store data from frequently accessed sites in order to cut back on overseas transmissions, saving time and money. However, they are used for surveillance in Singapore.

* Firewalls, or massive blocking of overseas sites by screening domain names. This is not being done at the moment in any of the countries surveyed, but, in the event of civil unrest, Chinese authorities could easily "pull the plug" of Internet dissidents by blocking all sites without the ".cn" domain name extension.

* Blocking access to lists of banned sites. TELA's list of 1,000 banned sites could be a starting point.

* User agreements, such as the one used in the People's Republic of China, spelling out so-called acceptable use policies for Internet subscribers.

* Banning Internet access to overseas sites by telephone lines, as is the case in Vietnam.

* Taking control of the domain name process, as China has done.

* Controlling subscription rates in such a way as to make them prohibitively expensive for all but institutions and elites.

* Restricting Internet subscription rights to individuals and institutions that can be trusted not to abuse Internet privileges.

This article has not been a call for regulating Internet content. It has been a presentation of ways in which the Internet can be regulated, if the community should decide to go in this direction. Whether or not such a move is warranted, however, is strictly a decision for the citizens of the SAR..