Now that has changed, thanks to the Internet and the World Wide Web, plus the advent of easy-to-use software that enables anybody with an Internet connection to publish a blog. You no longer have to depend on a professional intermediary to hear the voice of that Congolese park ranger. You can visit his blog.

More specifically, you can read the blogs of rangers like Elie Mundima who works to protect mountain gorillas in Virunga National Park, and “Atamato,” whose job is to protect Virunga’s last remaining hippos. These men write regularly about their jobs, the people they work with, and the issues they face. They upload pictures and video. They are speaking directly, in English, to anybody in the world who might be interested. They have taken media creation into their own hands and are no longer dependent on any media professional for them to speak to a global audience.

Niche Blogs

Weblogs, better known as “blogs”, are a kind of website in which the author posts text, photos, or other media in reverse-chronological order (newest at the top). Each entry has a unique web address and blog publishing software makes it easy for bloggers to link to other websites and blogs, creating a “web” of conversation across the Internet. Most blogs today are published with user-friendly software that requires little more technical knowledge than what one needs in order to write and send e-mail. Blogs can be published for free on many free blog-hosting services that now exist in many languages around the world.

The San Fransisco-based blog-tracking company, Technorati, now counts 73.4 million blogs worldwide, although people who study the global blogosphere believe this fails to include several million more blogs written in such languages as Chinese, Arabic, Hindi and so forth. Blog-hosting companies and search engines in China have counted as many as 30 million blogs in China alone.

Most bloggers do not set out to challenge news organizations for mass audiences, contrary to what some news editors may fear. Most write (or post photos, video or audio) to share their lives and interests with friends and family. Many others use their personal blogs to share ideas and brainstorm with their extended circle of professional colleagues and peers who are interested in the same subjects or issues - subjects that tend not to be a focus of mainstream media stories, but which are nonetheless of interest to hundreds and sometimes even thousands of people. Such “niche” blogs are considered very popular if it has a daily readership in the low thousands. From time to time, however, personal or “niche” bloggers with normally small readerships find themselves in the middle of a major event that happens to be of interest to mass audiences and the mass media ?a tsunami, hurricane, coup or war. Or they happen to be expert in something that suddenly becomes important to large numbers of people - like constitutional law, or computer typeface, or seismology, or Bird Flu. Suddenly complete strangers are sending around the web address of their blog and journalists are quoting from it in news stories.

Bridge-blogging

The media world first awakened to the global power of first-hand, personal, “non-professional” accounts when a young Iraqi architect using the pen name “Salam Pax” captivated readers around the world with his personal accounts in English of what it was like to live through the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Since then, tens of thousands of people around the world have emerged to become what we call “bridge bloggers”, people who blog about what is happening in their country for a broader global audience.

A classic example of “bridge-blogging” can be found on the blog of Mahmood Al Youssif, an engineer living in the Gulf state of Bahrain. His blog “Mahmood’s Den” provides biting (and often sarcastic) analysis of Bahraini politics in detail not available in the mainstream English-language Western press - or in Bahrain’s official English language press, for that matter. Mahmood, an entrepreneur, makes no money from his blog. (see: http://mahmood.tv )

He blogs to participate in his region’s political discourse, and also to act as a badly-needed bridge between East and West. As he writes on his blog’s “About” page: “Now I try to dispel the image that Muslims and Arabs suffer from - mostly by our own doing I have to say - in the rest of the world... I am no missionary and don’t want to be. I run several Internet websites that are geared to do just that, create a better understanding that we’re not all nuts hell-bent on world destruction.”

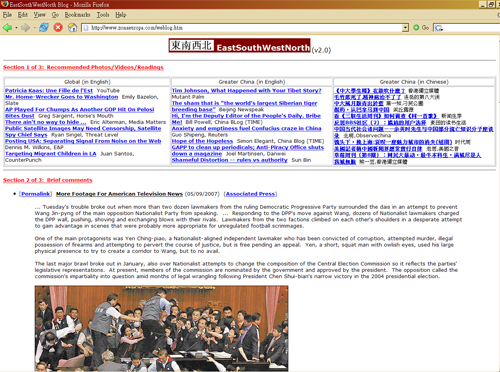

In Hong Kong, media researcher and translator Roland Soong uses his blog “EastSouthWestNorth” as a bridge between the Chinese-language Internet and the English-speaking world. (see: http://www.zonaeuropa.com )

Speaking at the 2006 Chinese Internet Conference in Singapore, Soong explained how he uses his blog to bridge between the “two different worlds” of English-language news and Chinese-language news. He pointed out that for many reasons, the English-language international media covers China in less detail than the Chinese-language media (including media from Hong Kong and Taiwan who report under much more free conditions). Much of the China news coming out in English is delayed, and Western journalists tend to have different perspectives on news events in China than Chinese people do. His goal is not to replace the English-language mainstream media but rather to supplement it, and specifically: “(1) to make a difference in specific cases and (2) to create an awareness that things may be more complex than it seems.”

Blogging has become very popular in mainland China, despite Internet censorship by the government as well as by private companies responding to government pressure. While censorship makes it difficult for Chinese bloggers to be as overtly political as in some other places, many Chinese bloggers nonetheless write about many things that cannot be found in China’s mainstream media. Increasingly, Chinese blogs have become the place where controversial stories first appear and capture public attention - then once the Chinese Internet is buzzing about them, journalists can justify covering these stories for mainstream Chinese media. In a recent survey I conducted of 72 foreign correspondents who cover China, 90% said that they follow blogs from or about China - written either in Chinese or English or both. More than half said they check Soong’s blog, as well as Danwei.org , another English-language bridge blog that frequently translates content from the Chinese-language blogosphere, at least weekly.

The journalists surveyed made it clear that they view the blogs as sources of story tips, ideas, and opinion which need to be followed up and confirmed; just as a journalist won’t do a whole story around unconfirmed information given by one source, journalists I surveyed do not directly report as fact what they read on blogs.

Create Synergies

It is true that professionals have lost control over how the public gets its “news”. At the same time, professional journalists still have a vital role to play in informing the public about world events. Most people do not have hours of spare time to scour the web each day in search of credible information. People also need help putting things in context. Journalists have a valuable service to play when it comes to finding, verifying, and contextualizing information. Objectivity and impartiality are also valuable. To return to the story of the Congolese park rangers as an example: We want to hear from the Congolese park rangers, but we also want accurate and balanced news reports about the political situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, brought to us by professionals whose job requires that they not have vested interests in conflicts, politics, or trade in that region.

There are many experiments in new forms of journalism that aim to create synergies between the energies of citizen media and the experience and resources of professional journalism. Global Voices Online ( Globalvoicesonline.org : a site that I co-founded) is managed by an international team of bloggers who select, contextualize, and increasingly translate the most interesting content found on blogs around the world except North America and Western Europe. The non-profit project’s core funder is Reuters News Agency, whose management find the content on Global Voices to be a valuable source of information for their journalists as well a valuable complement to Reuters' journalism. This Spring, Reuters launched an African news website which provides links to the latest writings of African bloggers as selected by Global Voices editors.

Another innovative new project is NewAssignment.net, founded by New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen, which seeks to create a new model of what he calls “pro-am journalism”, collaboration between professionals and amateurs that can help serve public knowledge and discourse on important issues. The first project called “Assignment Zero” has just been launched in partnership with Wired magazine. (see http://zero.newassignment.net/ )

Thus the world is changing, and the process of journalism is changing with it. As journalists, we must not fear change. Rather we must embrace all new developments that can help us serve the ultimate purpose of journalism.

If the purpose of journalism is to serve the public discourse, it is in the public interest for us to share the journalistic process with fellow citizens who have information, experiences, and ideas to contribute. The Internet makes this possible in ways that were much more difficult before - except to a limited extent with talk radio.

The prospect of sharing parts of our “job” with non-professionals may be frightening to many journalists who are used to doing things a certain way. But if we are being true to the ideals of our profession, then we should welcome the fact that global information flows - and thus the global conversation - are being democratized. Today’s journalists have a unique opportunity to shape the future of a more democratized, participatory kind of journalism.